On Photography and Copium (Part 2)

In part one, I made parallels between the film Nightcrawler and the main points of Susan Sontag’s photography essays. Her next essay, “Melancholy Objects,” has so much cultural baggage to unpack that I wrote a completely separate post for it. Or rather, I have a lot of cultural baggage to relate to it.

III. Melancholy Objects #

In “Melancholy Objects,” the 3rd essay of On Photography, Susan Sontag claims that photography is an inherently Surrealist artform, and that photography is a sad affair.

Unlike paintings, great photography is often haphazard and sometimes accidental: a celebration of the base, the mundane, and the novice. The basis of a viral video is how randomly it can blow up. Most people never expect their Vine, or TikTok, or whatever film, to reach millions of watchers. Sontag says, “In the fairy tale of photography the magic box insures veracity and banishes error, compensates for inexperience and rewards innocence.” She also wrote, “Surrealist manipulation or threatricalization of the real is unnecessary, if not actually redundant,” subscribing to the idea that reality itself is absurd.

As countries develop and start to enjoy the infrastructure and standard of living that people used to dream of when they mentioned the “American Dream,” we will see Sontag’s analysis come to light. Modern media, which includes photography, will face time-old moral dilemmas, but with a twist.

Many photographers participate in “class tourism.” Celebrities, nudes, and poverty are all ripe for vouyeristic exploits. “The view of reality as an exotic prize to be tracked down and captured by the diligent hunter-with-a-camera has informed photography from the beginning, and marks the confluence of the Surrealist counter-culture and middle-class social adventurism.” What is the driver behind “cancel culture” and affirmative action? Sontag says that photography has a democratizing effect. I think social media takes it a step further and brings on the democratization of justice.

If everyone is loudly talking at the same time so that nobody can hear each other, if everyone buries each other in a slurry of downvotes, is talking too loudly and ostrasizing people a form of censorship, or just a way to discipline the ignorant? Should we leave it to natural selection so that only the strongest voices survive?

Photography as a driver for social justice #

Insofar as the muckrakers got results, they too altered what they photographed; indeed, photographing something became a routine part of the procedure for altering it.

Sontag mentions several projects that Americans initiated for activism. One such project was conducted by the Farm Security Administration, who hired and trained photographers to go to rural, low-income groups. The documentors had to, in pictoral fashion, show the poor as dignified human beings. In essence, convincing the well-off that not everyone got to eat cake every day, and that poverty really sucks.

The act of photographing and filming has become a moral duty. A woman illegally walked her unleashed dog through a park, and a black man recorded a video with his smartphone. The woman started hurling racist insults. The video went viral, and she got fired from her job. While it is well deserved, it shows how pointing a camera is a threatening act, an act of aggression. Filming, recording, securing truth and power, facets that Sontag emphasizes in all of her essays.

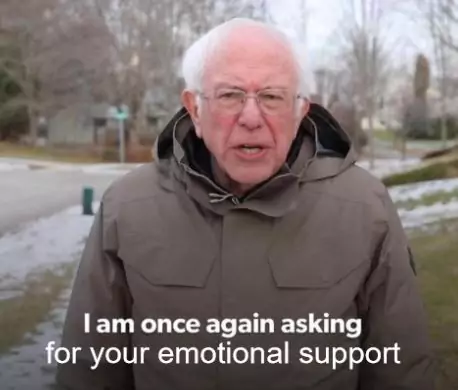

Sontag mentions how people love to share and read quotes, and even more so when they’re captioned to a photograph. She describes what sounds like the precursor to the meme: “In principle, photography executes the Surrealist mandate to adopt an uncompromisingly egalitarian attitude toward subject matter (Everything is “real”). In fact, it has —like mainstream Surrealist taste itself—evinced an inveterate fondness for trash, eyesores, rejects, peeling surfaces, odd stuff, kitsch.” Photographs with quotes are taken more seriously than novels and literary narratives, because photo-fiction has reached the same credibility as any document.

The magnetism of photography, of being relatable and true and yet totally scripted and staged, stokes debates about what information we can trust. I wonder what Sontag would have to say about deep fakes and AI face generation.

Fear of Missing Out #

Through photographs we follow in the most intimate, troubling way the reality of how people age… Photography is the inventory of mortality… Photographs show people being so irrefutably there and at a specific age in their lives…

She claims that the Old World had a better relationship with stability and loss. Europeans photographed subjects that were expected to stay for awhile. The wealthy stay wealthy if they don’t get wealthier, buildings are hundred of years old, and life is a deliberate march. Conversely, Americans took photos to save what will be gone. In fast food and throwaway culture, or more simply said: as people without a culture, they hurried to preserve the remnants of consumerism. “Fewer and fewer Americans possess objects that have a patina, old furniture, grandparents’ pots and pans—the used things, warm with generations of human touch…”

While Americans have always been crazy, we have a tendency to worship entrepreneurs and “the hustle.” Insane dreams of becoming so filthy rich that you can disregard the rules. Elevated expectations from witnessing photo and video evidence of the not-so-secret lives of millionaires. Photography and modern technology strengthen that black hole of discontent.

It’s not enough to be a decent novelist. You have to dream of landing a TV deal for your book and raking in the cash, because books are worthless without a Netflix show. It’s fine to dream about winning the lottery. Of course it’s all a joke, an undercurrent of wistful thinking, a very real desire to have a stable life.

In the past, a discontent with reality expressed itself as a longing for another world. In modern society, a discontent with reality expresses itself forcefully and most hauntingly by the longing to reproduce this one.

Sontag approaches an interesting zenith in her analysis, about the urges of society, about how photography soothes anxiety. I think if she had lived a little longer, she’d be able to chuckle at the era of digital frenzy. But she overlooks something. We make videos and take selfies out of discontent, not to reproduce this crappy world which exists, but the world of the beautiful and the rich.

It is simply an act of building a nest out of despair and boredom, of cobbling hair and fur and hoping that we’re warm and functional. Hoping that we lay the foundation for a nest egg, a seed that will grow and whisk us to the realm of the wealthy. To be patronized by a conoisseur of art, a sugar daddy or mommy, to be lifted into the ark of paradise. To join the court of a modern dynasty, where the rich transact with paintings and prints instead of money.

The urge to take photos is a survival instinct. Whether this “nest” is big enough to be an alternate reality, or we simply enjoy possessing a prototype of an idealized reality under our control, is a question for each person to decide.

Depending on how optimistic you are, being relegated to primitive survival instincts is either degrading, or beautiful. Some people call it copium, a portmanteau of cope and opium.

More often than not, the sub-reality that we create can easily turn grow out of control. Once it’s posted online, work is no longer owned by you. Your slice joins the ecosystem filled with other consumers. Your creative IP cannot be monetized if people can get it for free. Good artists copy, great artists steal.

So, how to get attention without sacrificing your soul or your money? That’s how photography fills the void. Sharing a photo is not as soul-crushing as being untalented at drawing or untalented at writing and receiving lukewarm criticism for either. In photography, the subject, not the artist, takes responsibility for being interesting. A grainy shot of your own genitals at least has some value (just, when you point the trigger at yourself, don’t blame anyone else for your mistakes).

Do we take pictures for pleasure? Perhaps. Why do we share and post them? Unlike in the past, where photos were collected in much the same manner as stamps, photos have become the baseline for conducting business and for public interaction. It is necessary, in this day and age, to have photos if you want responses and engagement. If you don’t want to participate in social media, you might as well not exist.

Let’s not forget the therapeutic merits of engaging in art. When we share photos, we drive our own social justice. Before we can start a Kickstarter, a Patreon, or a GoFundMe, it starts with the assertion of the individual in the soup of humankind. Smile, say cheese, snap.

—tomorrow we shall be able to look into the heart of our fellow-man, be everywhere and yet be alone; illustrated books, newspapers, magazines are printed—in millions. The unambiguousness of the real, the truth in the everyday situation is here for all classes.

—László Moholy-Nagy (1925)